Like many partnerships that last a lifetime, Kathy and David Glasgow got off on the wrong foot.

The couple, who are now aged 89 and 88, found themselves eying each other up while on jungle camp in Papua New Guinea with SIL International, an evangelical organisation serving language communities across the world.

American-born Kathy had excitedly caught the vision to “go forth into the field and lodge in the villages” (Song of Solomon) while studying at Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. She had gone to PNG with SIL with her fellow student, Darlene Bee, to work on one of the many languages needing God’s word.

Having decided at 17 to be a missionary, Dave felt called to work among Aboriginal people but was sent PNG to wait until SIL/Wycliffe (the two organisations that work together) were ready to launch what they would call the SIL Australian Aborigines branch.

What became known as the Australian Society for Indigenous Languages (AuSIL) officially started on 19 June 1961, in the small town of Barnawartha in Victoria with a small group of people dedicated to the study of Aboriginal languages and literacy work.

So as Dave prepared to speak at AuSIL’s online celebration of its 60th anniversary on Saturday, the first of several such events, Eternity asked the Glasgows about the foundations of their legacy. This substantial body of work includes Scriptures in Burarra language as well as the Plain English Version for Aboriginal people who speak English as a learned language.

But as extraordinary as this life partnership turned out to be, it was far from love at first sight, as they both confess.

Dave first caught sight of Kathy while she was training at Belgrave Heights Christian Convention Centre in Victoria with her fellow student, Darlene Bee. When Kathy and “Bee” stood up to be introduced as staff, Dave, as a young bachelor looking for a wife, thought “well, the short one’s okay but the tall one’s hair is too frizzy.’ (Kathy had got a “perm” to last her as long as possible in the jungles of New Guinea.)

Dave didn’t look all that eligible either to Kathy either when they met again in PNG.

“He really looked like a wild, woolly bachelor at that stage, wearing coveralls and bringing along the sand from the mountains,” she notes.

He blurted out, “Do you believe in going for walks?”

They began to soften to each other when Kathy’s widowed mother, who was serving in the PNG publicity branch, noted that Dave did really good work in editing a survey report on the Maprik Language, and Dave warmed to Kathy’s personality, eyeing her from a distance for several months.

“I felt very much attracted to Kathy, but I didn’t know how she would feel about me, and about leaving the language work she had begun. I wanted to talk to her about it, but every time I saw her, she was either with her mum, or her working partner or both.”

When after many obstacles Dave finally got the chance to talk to Kathy, he blurted out, “Do you believe in going for walks?”

“And he’s been saying funny things ever since,” comments Kathy drily as we sit at their kitchen table in Darwin.

“I said ‘yes.’ And when he came up and he took my hand as we crossed the muddy road and stepped across the ditch and before long, he said, ‘I never dreamed I’d fall in love with a girl with such a big nose.’ I just burst out laughing.”

Dave comments: “That clinched it for me. I thought if she can take that sort of a joke, she’ll do me.”

“You know, if you got to live out of your car, certain things happen.” – Kathy Glasgow

Kathy resumes: “So we went for walks and we talked about everything. I mean, he’s a real bushy. And he said, ‘would you be happy if we use the same bath towel’? I said ‘no,’ but actually a few years later when we were in Australia, and travelling overland with kids in the car as well, any towels were thrown across the top of other gear in the back, to dry, and I didn’t mind at all – we just all used the same towel. You know, if you got to live out of your car, certain things happen.”

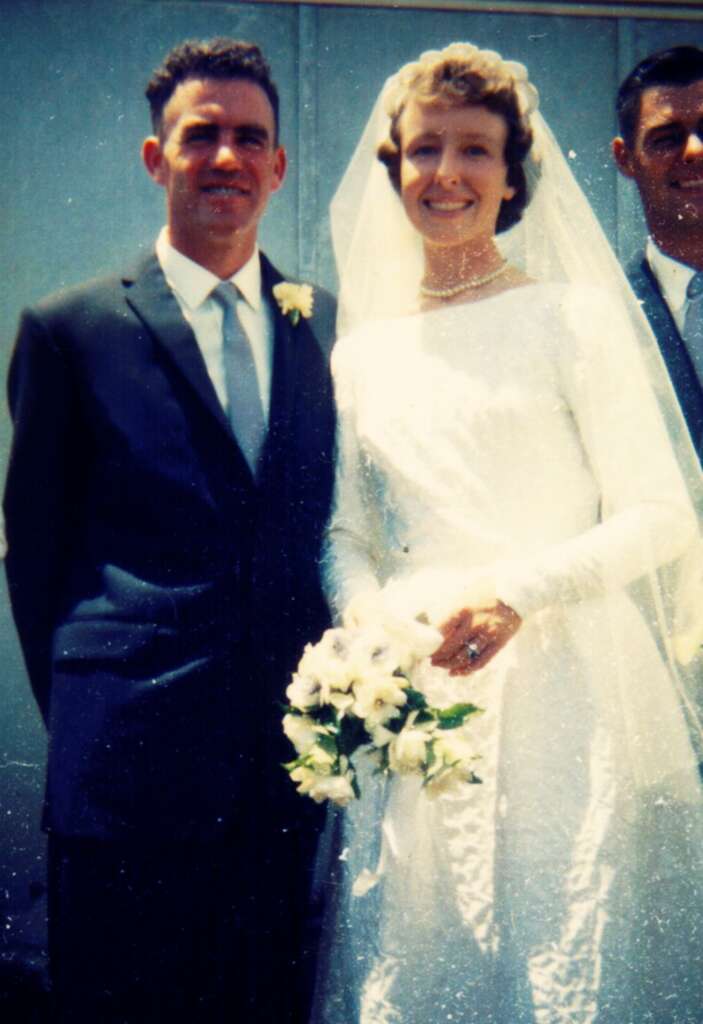

Kathy and Dave on their wedding day, November 1961

The morning after they announced their engagement, in June 1961, Dave received a telegram telling him to come to Barnawatha South, in Victoria, for the inaugural meeting a week later of what was then called the SIL Australian Aborigines branch.

“We were both called and I loved it so we both dove in together.” – Kathy Glasgow

It seems that once Dave had found himself a promised wife, things could begin. After the inaugural meeting, they returned to PNG and were married in November 1961. All packed up, they left PNG on their honeymoon, and went to Maningrida in Arnhem Land, in April 1962.

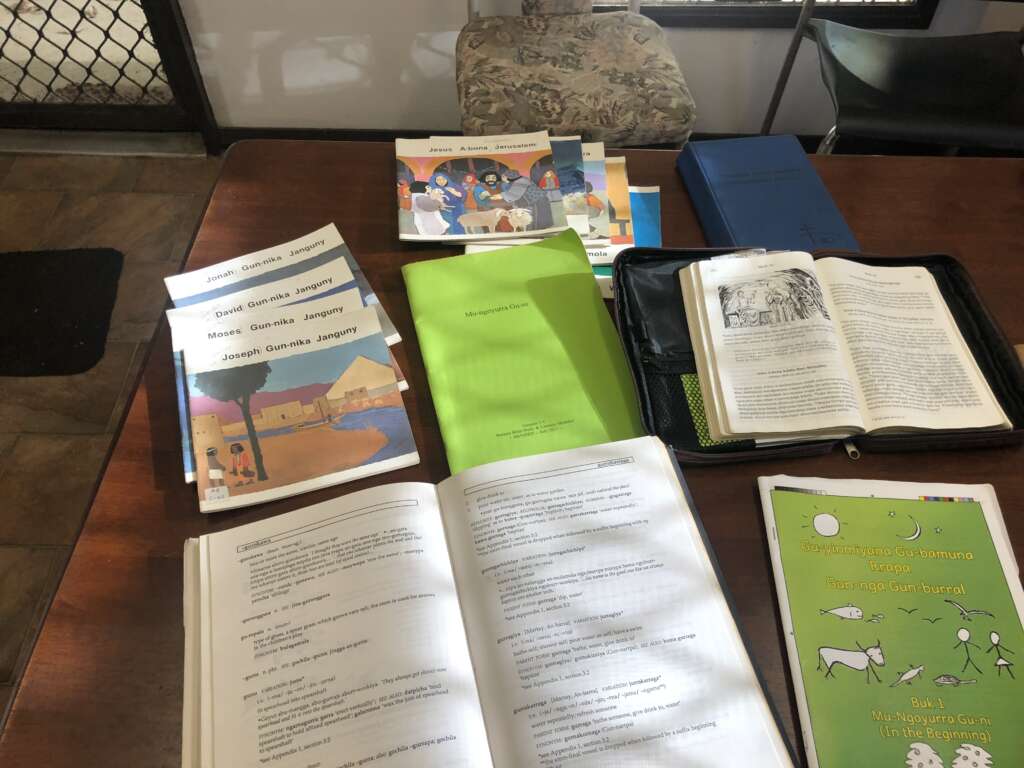

Over the next 29 years, they worked on Scriptures for the Burarra people, producing a New Testament, Old Testament portions, an 800-page dictionary as well as five Bible study booklets that are currently being reprinted by Bible Society for the next generation.

“We were both called and I loved it so we both dove in together,” explains Kathy.

“Our first home was a little car tent in the Burarra camp, with the people whose language we wanted to learn. We were so fortunate that they gave us permission to live with them. The Aboriginal people are very accepting, and they adopted us into their families.

“There was a sawmill there at Maningrida, and the very first day Dave got some timber and built us a nice big table that was our kitchen, and our office, and everything, under the shade flap at the front of the tent. Inside the tent, the roof sloped, and you couldn’t stand up, except at the entrance. The tent had no floor, and our two army cots were on the sand, complete with sandflies that loved our foreign flesh. But after a good dose of bites, we built up immunity.”

Kathy and Dave’s car tent at Maningrida

Asked if it was a challenge to adjust to such living conditions, Kathy says: “Well, I wouldn’t say it was what I was used to. I’m a city girl from St Louis. But when you’re young, you just do it. And remember, I had gone to Jungle Camp. I look back now though, and I’m amazed. Because I love staying home, where I know where everything is.

“I think women like to make any place home though – organised so people can have space to think, and do what they have to do.”

After about six weeks of living in their bush camp, first Kathy then Dave caught hepatitis because they couldn’t keep the flies off their food. It was virgin bush, and before the introduction of the dung beetle.

“Once Kathy’s hepatitis was diagnosed, we both went into Darwin,” says Dave. “She went into hospital there and I was able to buy some building materials and send them out on the supply ship, then I went back to Maningrida, where I started building us a bark hut with flywire and a concrete floor.”

“You had to boil the meat up in a salty brine to preserve it, you know, like the explorers ate salted pork.” – Dave Glasgow

“Burarra young men were helping me – experts in cutting sheets of stringy bark from the tree. I did come down with hepatitis, though. So had to rest a lot, and eat lots of tinned corn beef for protein to help me recover.”

“Staff at Maningrida could order fresh meat and veggies to be flown out every fortnight free of freight charge, and we were allowed to do that, too. But we could only order what we could eat in a few days, because the second-hand kerosene fridge we had bought cheaply in Dubbo, was sent to Glasgow, Scotland, instead of to the Glasgows in Darwin!”

Until the shipping company tracked them down and sent it to Maningrida, they had to “boil the meat up in a salty brine to preserve it, you know, like the explorers ate salted pork. It keeps for yonks,” explains Dave.

“So you had to just go with the flow,” adds Kathy.

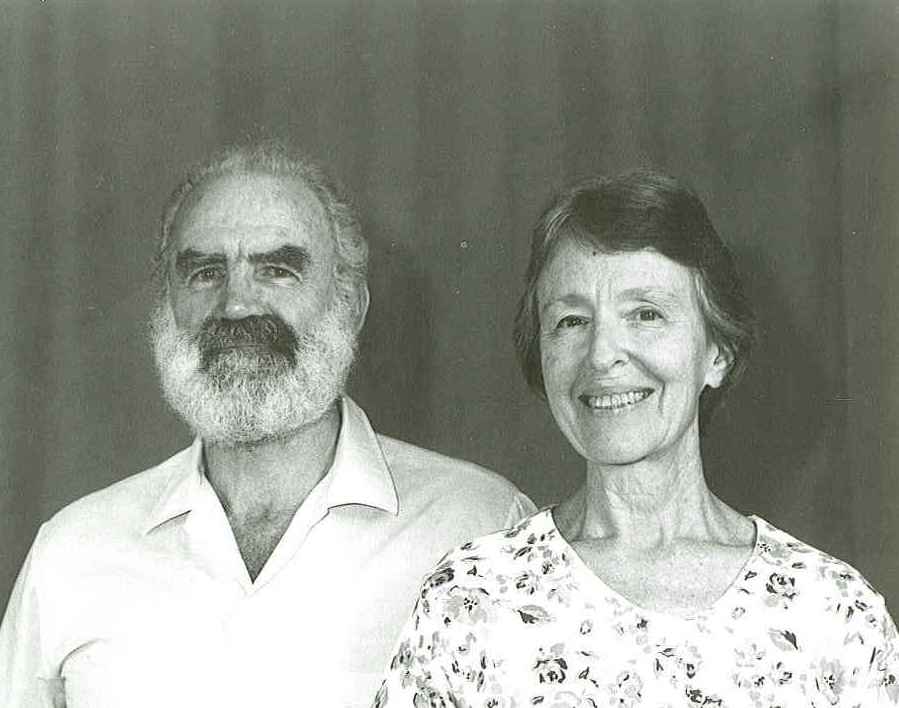

Dave and Kathy at the dedication of the Burarra NT at Maningrida in 1991

In those early days, Kathy and Dave were just collecting Burarra as they occurred in sentences, writing each word down with examples on a separate card.

“My work partner in PNG was very smart,” Kathy says, “and she had worked out a punch card system, which Dave and I were using – based on the same principle that computers work on today.

“We could use long knitting needles to pull out the cards with certain sounds to determine with sounds were phomenic [units of sound], and so would require a letter in the Burarra alphabet.”

“Three things the people really appreciate: when someone learns to speak their language; when someone goes away, but always comes back; and when someone has the true story.” – Kathy Glasgow

Within six months, the couple found that they could communicate better if they used their own level of Burarra rather than try to understand when Burarra people spoke English.

“We were determined to learn it, so the best way was living right in the bush camp,” says Kathy.

Adds Dave: “We’d hear people having an argument in the middle of the night and we’d learn language while lying in bed!”

Although there were some misunderstandings over what the “odd white people” could do for them, Kathy says the local people were patient and accepting.

“One time, our tribal brother and very important leader complained that we were no longer selling kerosene, as we used to. We had a good relationship, so I called his bluff, explaining that when we did sell kerosene, he wanted us to give it away free, like an anthropologist had done. So we quit selling altogether because it was too much for us anyway. As I said this, a little smile came across his face, and he came to appreciate that we were in it for the long haul, to give them God’s word.

“Three things the people really appreciate: when someone learns to speak their language; when someone goes away, but always comes back; and when someone has the true story.”

The illustrated Bible in Burarra, right, Burarra dictionary, front, and Scripture booklets in Burarra

Kathy continued to work on the Burarra Scriptures while they were in Darwin later, when Dave was serving as Branch director for about eight years. Then back at Maningrida, and working with a total of about 20 ‘precious’ co-translators, the Burarra New Testament was completed after many checks, and was published and dedicated in early 1991.

Soon after the NT dedication, Dave’s new job as adult educator took them back to Darwin. And after a reprint of the Burarra NT in 2008, Kathy made an audio recording of it, which, with the sound beautifully fine-tuned and a super app created for it, all by AuSIL colleagues, has been widely listened to and appreciated by Burarra speakers.

An anthropologist later told them that while he was working out at Maningrida he heard Kathy’s voice all the time as he walked through the camp.

Kathy Glasgow holds the claw of a crab, date unknown

After they retired, Dave and Kathy continued to make regular trips to Maningrida, and they went around all the homelands, sharing God’s word and encouraging the people to use the audio.

“And anyhow,” one woman in a neighbouring dialect homeland, said, ”You made this recording in Darwin, but people everywhere are listening to you.”

Yes, some people of other dialects, who know Burarra, will listen to the Burarra app. But there are many who cannot and would not use the printed Burarra Scriptures, saying they’re only for the Burarra people.

As Dave was puzzling over this, he began to think about writing some Scriptures in easy English.

“About 2007, I was at Maningrida, and I tried a little bit from first Timothy with a Ndjebbena speaker. She was excited about it, and she called out to her husband, who was a Kunwinjku speaker. He came over and she said, ‘listen to this’, and got me to read it again.

“I thought ‘that’s great,’ so after I came back I did the whole of first and second Timothy. I sent it to different Wycliffe translators around the place to ask their people ‘What do you think of this?’”

Disappointingly, the response was almost zero, so he put the project on the back burner.

But when Kathy translated some Bible studies into Burarra, Dave decided to do the same studies in easy English. They were well understood by the speakers of the other languages at Maningrida.

That was the genesis of what became known as the Plain English Version, a Bible that is accessible to people who grew up speaking one or more Indigenous languages, and whose English tends to conform to the grammar and discourse rules of those languages. As coordinator of a team of translators, Dave has personally generated about 70 per cent of the PEV that is available today. About 70 per cent of the New Testament has been completed and some short excerpts of the Old Testament. The PEV Mini Bible app is available on Android here. Bible Society is currently recording an audio version of the PEV Mini Bible.

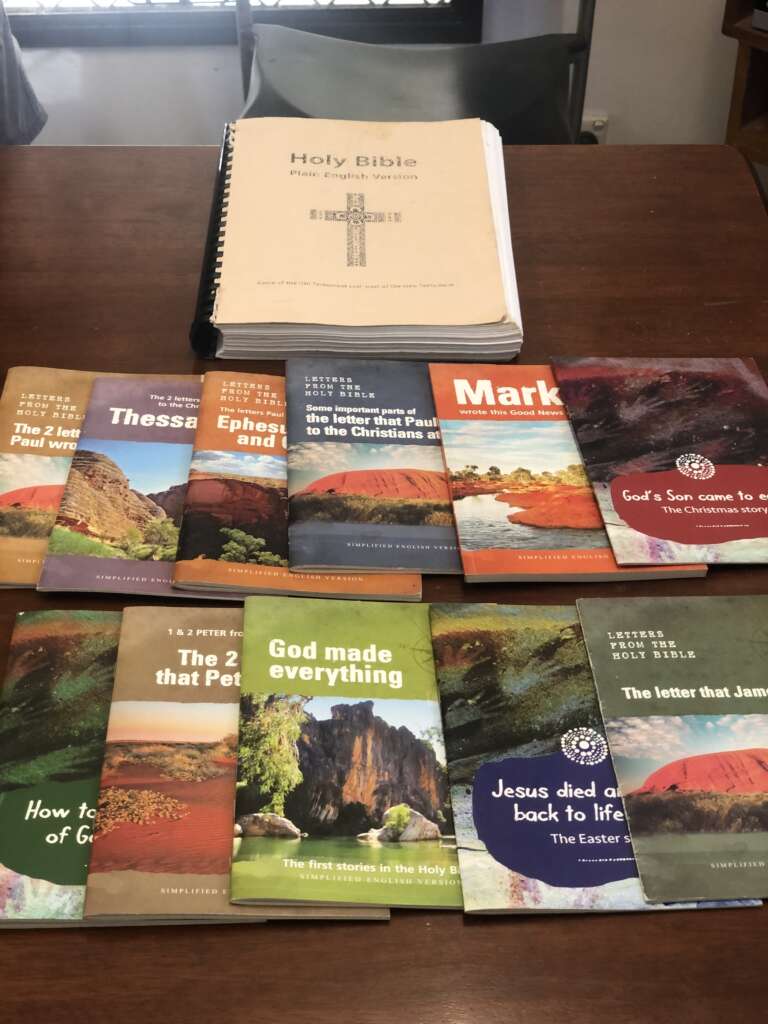

The Plain English Bible, at rear, with PEV Scripture booklets

“There isn’t one word there that I haven’t perused and thought about,” says Dave.

When I ask how his experience of translating Aboriginal languages helped with the PEV, he says there are two facets to consider.

“Firstly, you have to understand exactly what the original is saying. Secondly, you have to say it in a natural way.

“So I would work on the exegesis and get it in my head. Then I’d write it down, and it didn’t matter whether it took one sentence or 10 to say something, provided it conveyed the right concept. Then I’d go through it with the ABC principle. It has to be Accurate, has to be Beautiful, it has to be Clear.

“I would test it with people, asking content questions, and sometimes giving alternatives and saying, ‘Which way sounds better to you?’. And I’d get feedback. Very often too, in testing, I’d go to Burarra-speaking people and read it to them, and they’d say it back to me in Burarra. And if they got something skewed, I soon found out about it, and we’d work on it.”

Even now, Dave visits the AuSIL office in Darwin regularly to consult with Kathy Dadd, who has joined him in this project.

“I tell people I’m fading out, but Kathy there is fading in. She is already vetting stuff that I do, saying ‘you could improve this here’ and she’s right. Every time. Well, almost every time – I’ve got to stick to my guns sometimes.”

With her exuberance and his steadiness, his wife Kathy says she is amazed how well they have been able to work together on common projects.

Of their 60 years working together, she says: “We’re very different, you know. But we’re such a good comfort for each other, and we’ve learned to appreciate our differences. He’s doing the PEV, which doesn’t use all the deep abstract words of English. I think he’s got the harder job, explaining the deep concepts of Scripture in plain English. Whereas the Burarra co-translators could go back to camp, talk it over with the elders, and come back with ‘spot on’ words and phrases – language can be so beautiful!

“At the same time, our Aboriginal friends using the PEV say, ‘This really helps us understand’.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?